On Hatteras Island in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, there is a well-known T-shirt that reads: One road on. One road off (sometimes) makes fun of the ongoing conflict between Mother Nature and the small strip of pavement that separates the world from the slender barrier island.

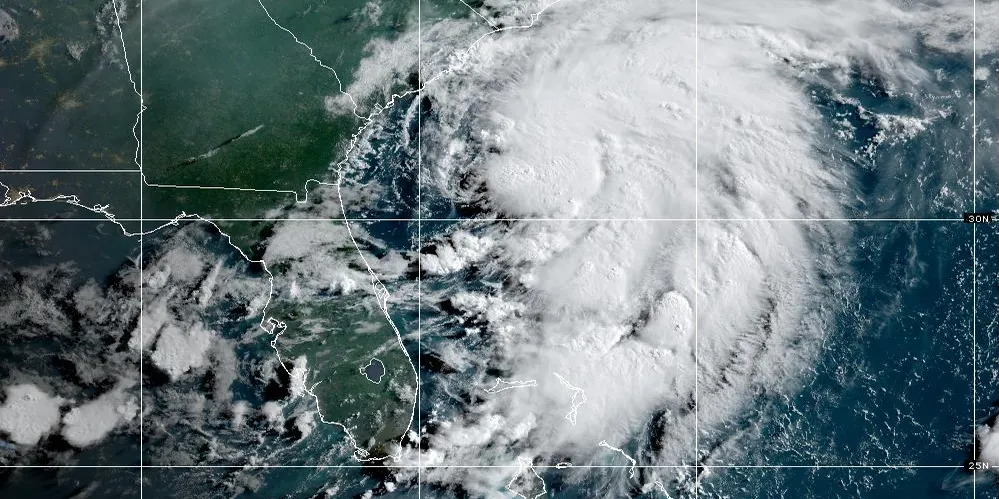

This week, Mother Nature is most likely to prevail.Although Hurricane Erinis is expected to remain hundreds of miles away, it is nevertheless causing waves of at least 20 feet to crash over the islands’ susceptible sand dunes.

Even in the absence of a hurricane warning, officials have ordered the evacuation of the Hatteras and Ocracoke islands because the little stretch of highway known as NC 12 is expected to be destroyed and washed out in many locations, leaving settlements isolated for days or weeks.

The roughly 3,500 residents of the Outer Banks have experience with solitude. However, the majority of the tens of thousands of tourists haven’t.

According to Reide Corbett, executive director of the Coastal Studies Institute, a consortium of several universities that research the Outer Banks, we haven’t seen waves that big in a long time, and the weak points have only gotten weaker over the last five years.

The Outer Banks are defined by water

In essence, they are sand dunes that, after many of the Earth’s glaciers melted 20,000 years ago, were tall enough to remain above the ocean level.

In certain locations, the barrier islands are up to 30 miles from North Carolina’s mainland. The enormous Atlantic Ocean lies to the east. Pamlico Sound is to the west.

Water, water, everywhere. According to Corbett, that strikes a chord on the Outer Banks.

The Outer Banks’ most densely populated areas are in the north, around Nags Head and Kill Devil Hills, which are exempt from the evacuation order. Hatteras Island lies south of the Oregon Inlet, carved out by a hurricane in 1846. N.C. 12 is the only way to reach the mainland from Hatteras Island. Ocracoke Island lies to the south and is only reachable by boat or airplane.

More than 60 years ago, the region’s first highways were constructed. As the Outer Banks transformed from charming fishing villages to their current state, replete with 6,000-square-foot vacation mansions perched on stilts, they began to flourish.

Maintaining the highway is arduous

In order to remove the continuously blowing sand, what appear to be snowplows and street sweeper brushes wait on the side of N.C. 12 on a pleasant day.

During storms, masses of sand and debris are washed onto the road by water from the ocean or sound that pierces the sand dunes. In more severe situations, storms have the potential to fracture pavement or even form new inlets that call for temporary bridges.

In order to maintain N.C. 12 open during the 2010s, the N.C. Department of Transportation invested over $1 million year in routine maintenance. Over the course of ten years, it also spent roughly $50 million on storm-related repairs.

However, the state believes that the tourism industry in Dare County, which encompasses the majority of the Outer Banks, generates $2 billion annually. Thus, the cleanup and repair cycle keeps on.

It takes time to fix. Ferries were required for two months after Hurricanes Isabel in 2003 and Irene in 2011, which both cut inlets into Hatteras Island. After more typical Nor Easters, N.C. 12 may still take days to reopen.

The erosion is constant

The island is affected by more than simply hurricanes. The Outer Banks are at risk from rising ocean levels brought on by global warming and the melting of polar ice. Every inch of sand matters in an area where the majority of the land is only a few feet above sea level.

Since 2020, the turbulent water has engulfed over a dozen residences in Rodanthe, which protrudes the most into the Atlantic. If the waves from Erin are as powerful as expected, officials estimate that at least two vacant houses will probably be lost.

The Outer Banks are still home

In the late 1970s, Shelli Miller Gates was a college student who worked as a waitress on the Outer Banks. She recalls homes without phones, TVs, or air conditioning. And she loved it.

I adore the water. I adore how wild it is. According to the respiratory therapist, it’s how I want to spend my life.

Many people embrace this way of life. The first three letters on state-issued license plates are among the many places the area’s proud abbreviation, OBX, appears.

The sense of community is enhanced by the seclusion. Gates has witnessed several instances of people coming together after losing their connection to the outside world. Additionally, there is always the attraction of living somewhere that other people only get to visit.

Everything is present. There are floods, lizards, and earthquakes. “Observe the impoverished individuals in western North Carolina,” Gates remarked. There are a lot of things that could go wrong. You need to choose a place that feels like home, in my opinion.